This post continues my interview with Rick Priestley. Part one can be found here.

How did WFRP come to be separated from WFB, and how did it go from being a supplement to being a full game in its own right?

I don’t recall that it was ever pitched as a supplement. The original version of Warhammer was a bit of a mish-mash – really a narrative driven skirmish toy-soldier wargame with a lot of role-play elements. At the time – 1982 – role-playing was the ‘hot’ new thing and we recognised that it was possible to sell almost anything with the words “role playing game” on. But by the time of the second – and then third – editions of Warhammer our ‘Citadel’ market had clearly settled down into something more like a conventional tabletop wargame. That meant the role-playing elements had been progressively dropped. We – which is to say Richard Halliwell and I – had a clear notion of the difference between tabletop wargames and role-playing games. I don’t imagine that Bryan Ansell’s view would have been any different. It was a natural progression to separate out the two things and produce a proper ‘pen and paper’ role-playing game to compete with Dungeons & Dragons, Runequest, Call of Cthulhu, Paranoia etc – all of which GW had produced under licence in the 80s. So, the idea of doing our own rpg was firmly established, and it was an obvious step from importing games, and then licensing games, to producing our own games. Needless to say, you make more money by selling things you make rather than selling other people’s products. There was the assumption that there was a great deal of money to be made – after all – just look at the mighty TSR and D&D! The reality would prove a little different. The market for rpg’s wasn’t quite as lucrative as expected, and meanwhile the market for our tabletop games – especially Warhammer and 40K – was going great guns! However, at the time we didn’t really know how things would pan out – the pivot towards 40K had yet to take place and the clear realisation that GW was going to become focussed almost solely upon miniatures sales hadn’t quite struck.

Whilst I can remember working on the manuscript for WFRP – and I can remember Hal contributing significantly to the early drafts – I don’t remember Bryan contributing to it at all. No doubt Bryan would have read and commented on material as it evolved. By the time we were working on what would become the fantasy rpg Bryan was already running a much larger company than the one I’d joined four or five years earlier. His time was mostly taken up with managing the business as you would expect. I don’t think Hal was actually working for us at the time – his contribution would have been done as been a commission – and a lot of my own time would have been taken up with the studio. There was a first draft produced at Eastwood, prior to us moving to Low Pavement and before the ex-TSR team joined us along with Graeme Davis. That was pretty much a complete manuscript as far as I recall, but the game was in need of further playtesting and the rules were an initial draft based on what playing either Hal or I had managed – so not a finished game by any means – but definitely a solid initial draft. At the time, I was in touch with Simon Forrest with whom we’d established a relationship and who I seem to remember was running a rpg fanzine – and I must have sent him material to read and play-test as part of the process. Simon is a lovely chap and joined us later as White Dwarf editor. Simon was a first-class editor whose standard of written English was second to none. His first response to my draft was to send me a two-page list of all my most egregious solecisms – including all the words I habitually spelled incorrectly – bless him. He later confessed he was taking the piss a bit (and who can blame him) but I promptly stuck the list up on the wall in front of my word processor and referred to it constantly. As a result, I never again misspelled ‘separately’ and will forever know that the plural of ‘Octopus’ is ‘Octopodes’! Which fact alone suggests that the bestiary section was well underway as it obviously included the dreaded ‘Bog Octopus’.

Everything for the first draft was written on the Rank Xerox WP (Hal would have sent in typescript hard copy which I would have transferred manually). I imagine it would all have had to have been completely retyped at some point into whatever format was needed for the Amstrad PCWs with which we were re-equipped when we moved to Low Pavement. I can’t think that we would have been able to make a transfer between the Xerox WP system and whatever we were using for the Amstrads (Word Star if I remember correctly). I wonder who got that job! It might have been me, but I suspect the incoming team just got on with it. I guess that we would have used the physical hard copy of the first draft as a basis, which would have allowed the team to refine and edit as we went along. We were all working in the same big open plan office, and I remember Jim Bambra working on the combat rules, and he must have come up with a snag with the hit location system, because we proceeded to kick ideas between us and came up with the ‘inversion’ system where a roll of 25 (say) for the hit became a roll of 52 for location. Anyhow, once the TSR guys came over – and Graeme of course – I largely stepped aside and got on with whatever other projects were on the go. Hal must have joined on a salary at about the same time, but I don’t recall that he had much to do with the rpg at that point either. So, from then on, the development of the rpg was down to Phil, Jim and Graeme, and was immeasurably the better for it! They would go on to develop the content that would make WFRP what it was, and which would feed back wonderfully into the world development for all the later versions of Warhammer as well as the novels and other projects.

Warhammer Fantasy Battle, first edition (1983) and second edition (1984), and Warhammer Fantasy Roleplay, first edition (1986)

I gather the Old World was already fully developed in your draft. This must have come not much more than a year after the very brief outline in WFB2. How did you flesh out the Old World?

I don’t really remember how it all started – but you can see how the idea of a Mittel Europe setting fits the idea of a sinister, haunted fantasy realm. It’s vaguely evocative of Dracula’s Transylvania and the tales of the Brothers Grimm with its dark, impenetrable woods, inaccessible mountains and wild places overrun with all kinds of potential for peril and adventure. I think the simple answer is I just sat down and did it – inventing the geography of the place in more detail and describing the various cities of the Empire. We incorporated Hal’s Marienburg-in-the-Wasteland as a neighbour of the Empire paralleling the Low Countries and with a mercantile history and maritime role similar to Amsterdam in the early modern era. I dug out a lot of books on medieval and early modern society. I always liked to root the fantasy world in real-world facts, so how long does it take to travel the roads and waterways, how long does it take to ride a horse from A to B, and how about coach inns and livery, how does it all work? Some of what I wrote echoes the Roman system of roads, way stations and travelling inns. Other aspects are inspired by early modern coaching. I don’t know why the setting shifted from strongly medieval to an early modern base – it was probably inspired by the contemporary model ranges as much as anything. It does introduce a lot of potential from Shakespearean actors to masked Highwaymen. I enjoyed describing the cities of the Empire with their distinctive – and generally rather fantastical settings – Middenheim, Altdorf, and so on. The idea was to create a background that was big enough and which had enough wilderness to locate all of the many threats that were already a feature of the world – Beastmen, Orcs, Chaos, etc. The Dwarfs were easy – they lived in the mountains in Tolkien-esque holds where they were locked in an unending battle with goblins. The Elves did feel a bit like they’d been crowbarred in – with the obviously pseudo-Tolkien Loren – but it all seemed to hang together well enough. I’ve never found that kind of world-building hard. To be honest I’d could sit down without the first idea of what to write, make a start and just go where it takes me. And that’s pretty much what I did!

First map of the Old World, from Warhammer Fantasy Roleplay, first edition (1986)

The nations of the Old World obviously derive in large part from historical European analogues. Why did you take this approach? Was it to incorporate historical miniatures? Was it just to draw on your historical knowledge and create verisimilitude? Were you inspired by Moorcock’s History of the Runestaff, with pseudohistorical places like Granbretan, Kamarg and Amarehk?

And also Robert E Howard’s Hyboria and the various world settings of Philip Jose Farmer’s World of Tiers, amongst many others, I’m sure! It was a fairly common approach in fantasy settings because it enables you to reference a pre-existing culture and keep things consistent and in character. It was originally something that was suggested by the model range, but because the model range was mostly medieval it fitted well into pseudo-European setting with the peripheral areas drawing in ‘Araby’ and steppe cultures – we made Huns at the time too. We cast a token Japan in the form of Nippon in the far east simply because we made Samurai, but it never really sat well with the rest of the setting. The High Elf Kingdoms is an obvious Atlantis and the western continent gave us the opportunity to put the Dark Elves somewhere specific – the Slann sat in the place of Aztecs and Incas.

Graeme Davis has said that he developed a number of the gods in WFRP, but several were already in the draft when he arrived. Can you talk about the creation of the gods?

From what I can remember – for the first draft, I named and wrote the basic in-world descriptions for all the gods up to the final section [of the published chapter]. I guess that text was worked over and expanded, but it’s all rather seamless, isn’t it! The final section includes the gods introduced via the Kaleb Daark comic strip by John Wagner and Alan Grant that was published in several of the Journals/Compendia. Those were definitely added and not in my draft. I don’t know where the idea for those extra gods [Malal and Arianka] came from – but seeing how there was a dispute about the ownership of that IP – and we were subsequently obliged to drop it as a result – I imagine it was just made up by the strip writers. The last page includes the Chaos god Khorne – but strangely no other Chaos gods – although they were certainly invented (by Bryan Ansell) and described by then, and – of course – we made models for the various daemons. I don’t remember whether Sigmar was in the original draft or not – very possibly not as the format is rather abbreviated and doesn’t have the usual list of attributes that I would have included. I did read Phil’s piece in which he explains how he invented Sigmar, so I shall defer to his recollection on the matter! Sigmar is essentially the state god of the Empire – rather like a deified Emperor in ancient Rome. In his case a deified tribal leader revered as the founder and patron god of the Empire – and that’s about it in the WFRP rule book. That little seed would certainly be something that was elaborated upon and built into a significant part of the Empire’s story by the rpg team.

The rest – which is to say the ones included in the first draft – are fairly obviously based on classical gods, Greek, Celtic, Norse or whatever. Some of the cult practice and generalised detail is drawn from archaeology or well-known cult practices in antiquity. The religious environment described at the start of the section on ‘Religion and Belief’ is inspired by classical and Hellenistic Greek cult practices – as distinct from Greek ‘myths’ which everyone knows about and which are akin to folklore. Actual Greek cults were far weirder – and could involve things like sparagmos and omophagia – and other quite sinister stuff. Later Apollonian cults parallel Christianity to some extent – holding that all gods are but aspects of a single supreme deity. Greek religion was something I’d studied as part of my degree – it was a Classics ‘unit’ but I snuck it in as a ‘free choice’ as part of my Archaeology course. That connectivity between respect for the gods and common-sense daily affairs was something I took from that.

I’m not sure whether any of those gods had any currency in Warhammer previously. I note the list doesn’t include Rigg, who was a creation of Hal based on his Lustria setting (and named after Diana Rigg obviously). Some of the gods are obviously gods of a place – localised deities melded into a pantheon – for example compare Taal the god, Taal the river and Talabecland (‘bec’ or ‘beck’ refers to a river from Norse – Land of the river god Taal). That’s the sort of thing I’d use to build up a world with a sense of a past, language and culture. That’s partly why Sigmar becomes so important – because Sigmar is the one god that binds the whole Empire together (akin to Emperor worship in Ancient Rome – Christians were persecuted because they refused to acknowledge the divinity of the emperor – in reality all kinds of gods were worshipped in the ancient world and I doubt that anyone really ‘believed’ in the emperor as a literal god – I suspect most people would have made the token submission and not given it a second thought.)

Esmeralda (Halfling Goddess) was part of my draft. Esmeralda was the name of my bicycle when I was a teenager – I painted it onto the side of the frame in big white letters! Sadly, Esmeralda got nicked one evening when I was working pumping petrol at a cash n’ carry in Lincoln and I had to walk the four miles home. One remembers these things. 😊

How did you develop the careers system?

The careers system was actually part of Hal’s original manuscript – the structural idea and many of the careers – but Hal was having difficulty working it into a playable system. I really liked the idea and thought it brought the world to life in a unique and rather clever way. So, when Hal more-or-less threw his hands up I decided to try and make it work. I think I managed it reasonably well, but along the way I had to expand the number of careers hugely to create intermediate careers along the different career branches, and naturally I added more branches as they occurred to me. In the end the careers section was huge! Tony Ackland started to draw a piece for every career, a gargantuan task, and I think he’d just finished when Bryan decided that we’d have to cut down the number of careers as we couldn’t possibly make that many new models to represent every career! I’m not sure whether it was me that did the pruning for the first draft or whether that was something the rest of the team got to do, but either way the number of careers was reduced to something more manageable. I honestly can’t remember what was cut, but Tony might as he had to draw them all!

Incidentally I noticed that Andrew Szczepankiewicz’s booklet for Blood on the Streets fits with a lot of later WFRP careers.

I don’t recall what Andrew Szczepankiewicz’s role was in the early evolution of WFRP. ‘Pank’, as he was always known, worked in the mail order department and it’s quite likely that he’d have helped out with playtesting, and he probably had an early copy of work in progress to refer to when he wrote that supplement.

For a while the Warhammer RPG was for a while called WARPS, the Warhammer Advanced Roleplay System, before undergoing a last-minute change to WFRP. Do you recall why the name changed?

I don’t remember that at all – often these things get working titles that get changed as we go along.

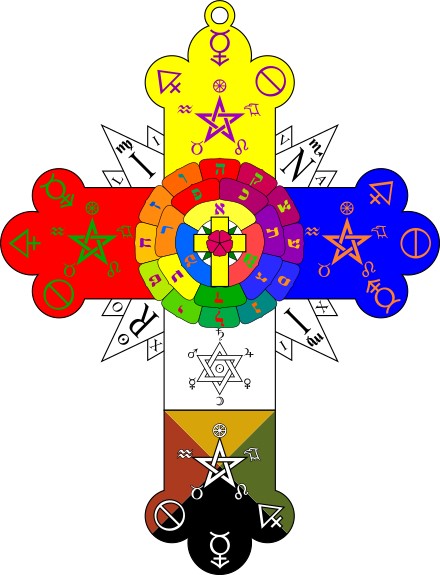

I was intrigued by your earlier mention of WB Yeats and Dennis Wheatley. In your revamp of Warhammer magic in 1989, which introduced the magical colleges, I noticed some echoes of early twentieth-century occultism. The colour wheel resembles similar wheels of the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn and some of the symbols seem to originate in occultism. I also detected the influence of Tolkien, Pratchett, the old SPI boardgame Sorcerer and the colour wheel in art. Could you share your memories of how the colours of magic came about?

I think this is something that is already covered very well in your piece on the evolution of colour magic, which includes a copy of what must have been Bryan’s original memo. As far as I remember, Bryan hit us with the idea as outlined in that memo. I guess I got the job! I would have thought about it and worked up the resultant White Dwarf article. I don’t know what gave Bryan the idea in the first place, but I suspect it was the title of the Terry Pratchett book The Colour of Magic (and probably no more than the title). It certainly could have triggered latent memories of that SPI game Sorcerer, which I had also played back in the day. In fact, I still have a copy of it somewhere. As you can see from that memo, the idea is rooted in the notion that rival colours have a kind of paper, scissors, stone relationship, and that the actual colour of the target is also part of that calculation. That’s essentially the same as Sorcerer. Thus, what colour you painted your models would affect their vulnerability to certain sorts of magic. I definitely recall that I thought that a very, very bad idea indeed. I thought that having magical vulnerability affected by a player’s choice of colour palette would inevitably define how models would be painted, robbing players of the ability to paint their armies how they liked. I also wasn’t confident that such a system could be balanced in such a way that there wasn’t just one ideal colour to paint everything, resulting in all Warhammer armies being puce, or bright yellow, or whatever.

Rose Cross of the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, interlocking gyres from Michael Robartes and the Dancer (1921), by WB Yeats

I worked up the pseudo-occult background by taking the cosmology for chaos and mixing it with bits of Hermetic lore. The idea of a colour wheel drawing upon the energy of chaos and forming that spindle or cone shape you see in the White Dwarf article is an image straight out of A Vision by WB Yeats: it’s a ‘gyre’ (as in the “widening gyre” in ‘The Second Coming’). When it comes to the influence of occultism upon the Warhammer cosmology, as here, I must stress that I wasn’t trying to introduce genuine occult elements into the game in any way. I was just plundering ideas about arcana to give the backstory colour and depth. My whole reworking of ‘chaos’ envisions a parallel astral realm – the realm of chaos – and you can see that idea expressed very well in Dennis Wheatley’s novel Strange Conflict; you also get elements of it within The Devil Rides Out. The idea of people having a spirit-self that can astral travel and meet other spirits or powers within the astral realm was pretty well-established hippy-nonsense. Carlos Castaneda and all that! I just wove it all together, populating the astral realm with daemonic forms drawn from human desires, hopes and fears: composite entities with mobile, interflowing identities. Compare with Forbidden Planet and monsters from the id, for example. What I didn’t know until I read a biography of Wheatley (The Devil is a Gentleman by Phil Barker – very much recommended) is that Wheatley interviewed Aleister Crowley as part of his research for his occult novels – and based the character Morcata in The Devil Rides Out upon him. As I’m sure most people will know, Crowley was a member of the Golden Dawn prior to establishing his own occult temple and developing his own magical system. Yeats was also a member of course. So, all these rather fantastical ideas come from the same basic place. There are any number of books about these things: the classic work on the history of the Golden Dawn is Ellic Howe’s The Magicians of the Golden Dawn.

Later, we’d take up the idea of colour magic and use it to create the card-based magic system for Warhammer 4 and 5, and I’d expand the idea of magic ‘colleges’ to describe actual places that may or may not partially reside outside of normal space-time – much as Terry Pratchett’s Unseen University does. The character and traits of the various colour wizards are inspired by the actual colours, but I suppose the grey wizards owe something to Gandalf!

Part three of the interview is here.

For my other interviews, see this link.

Title art by John Sibbick. Internal art by John Blanche, John Subbick, et al. Used without permission. No challenge intended to the rights holders.

And now I will always see Halflings on bicycles. My immersion is ruined forever.

Joke aside, thanks to you both for this very interesting and informative interview !

LikeLiked by 2 people

A fascinating read. Thank you very much.

LikeLiked by 1 person

WFB1 May 1983 (but 1982 at the back of the White box)

WFB2 January 1985

LikeLike

What are your sources for those dates?

LikeLike

Not tthe best

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Warhammer_(game)#Second_edition_(1985)

After maybe it’s December 1984 which will explain the discrepancy with advertising

For the month of WFB1 I can’t find where I had read that. But the reviews of Ken Roston is of this month.

LikeLike

WFB1 was released some time around May 1983, but I have never been able to pin down the exact month. See this post for details:

‘https://awesomeliesblog.wordpress.com/2023/07/01/it-was-forty-years-ago-today/

The rulebooks inconsistently give dates of 1982 and 1983, as they were written over that period, but the publication date was definitely 1983.

WFB2 came around December 1984-January 1985. I always date it to December, though I can’t right now recall why I prefer that to January. The source in the Wikipedia link seems to suggest January is more likely.

LikeLike

fascinating – just finished the GW book by Ian Livingston and Steve Jackson (UK)

LikeLike

Brilliant stuff! I remember reading Pratchett’s The Colour of Magic at a similar time to when I was discovering Warhammer, but I’m not sure I’d really connected that as being an inspiration for the Warhammer colour magic (which I thought was wonderful, in WFB at least).

And the stuff about the inspiration for the various Warhammer deities is absolutely fascinating.

LikeLiked by 1 person