I am delighted to say that Rick Priestley, co-creator of Warhammer Fantasy Battle, Warhammer Fantasy Roleplay, Warhammer 40,000 and much else, very kindly agreed to be interviewed for this blog. The first part of our conversation is recorded in this post, and discusses the early history of his fantasy gaming and the creation of Warhammer. The following posts will cover his recollections of WFRP and more.

I’d like to thank Rick for being so generous with his time and patient with my questions!

Could we start at the beginning of your fantasy and science-fiction games? Tell me about the Lincoln Order of Necromancers and the games you played in those early days. I appreciate this might test the memory after fifty years!

Thanks for the question. Yes, it certainly was a long time ago and memory is a tricksy thing, so you’ll have to bear in mind that what I remember may not be – probably isn’t – a complete or entirely accurate account. It’s just what I remember. So, that caveat aside, I’ll start off with the Lincoln Order of Necromancers – ie LOON – which was just the cover name that we gave to ourselves and our gaming friends for purposes of publishing Reaper: myself and Richard Halliwell’s first set of commercial wargames rules. It wasn’t anything other than that. I suspect the name was Hal’s (Richard Halliwell’s) idea and, anyway, we just used it in that context, it wasn’t a formal or even precisely defined group of people, it was just Hal and me and our wargaming friends in Lincoln. We weren’t at all interested in necromancy as such – but LOON does sound like a good fit.

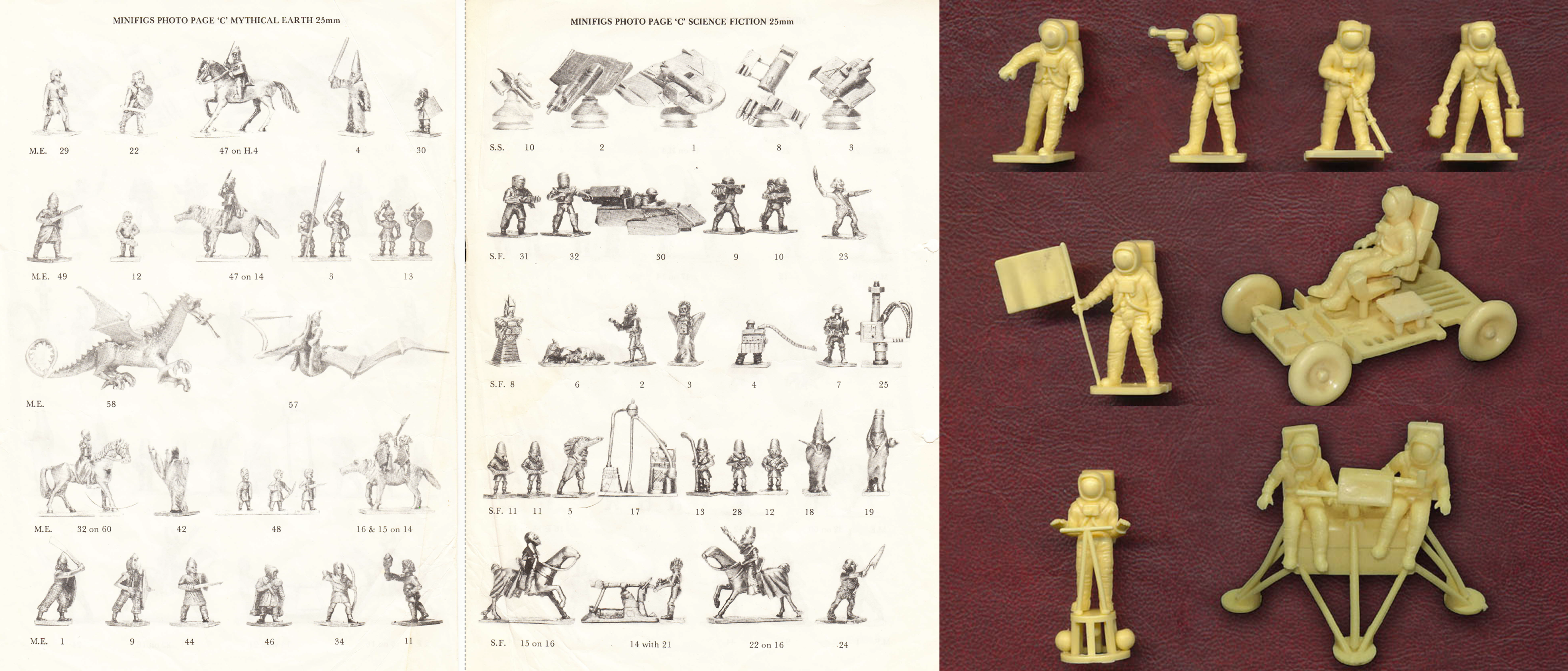

Hal and I, together with a few school friends, started inventing and playing fantasy and science-fiction wargames way before we ever thought of publishing Reaper, though, almost certainly going back to 1973 – ie 5 years earlier. I do remember that we’d talked about the possibility of playing wargames set in Tolkien’s Middle-Earth using historical ranges, with some thoughts about using smaller scale figures for Dwarfs and Hobbits and maybe scratch-building Ents – so the idea was in the air even before Minifigs (Miniature Figurines Limited of Southampton) released the very first commercial fantasy range – reviewed in the August edition of Airfix magazine 1973. That was the first complete fantasy range available in the UK – and possibly the world – although in the States Jack Scruby produced some fantasy figures at about the same time, and quite which came first no-one seems to know. In those days, it wasn’t possible to purchase from abroad, so our wargaming scene was very much what was made, produced and published at home; so, it was Minifigs all the way for us!

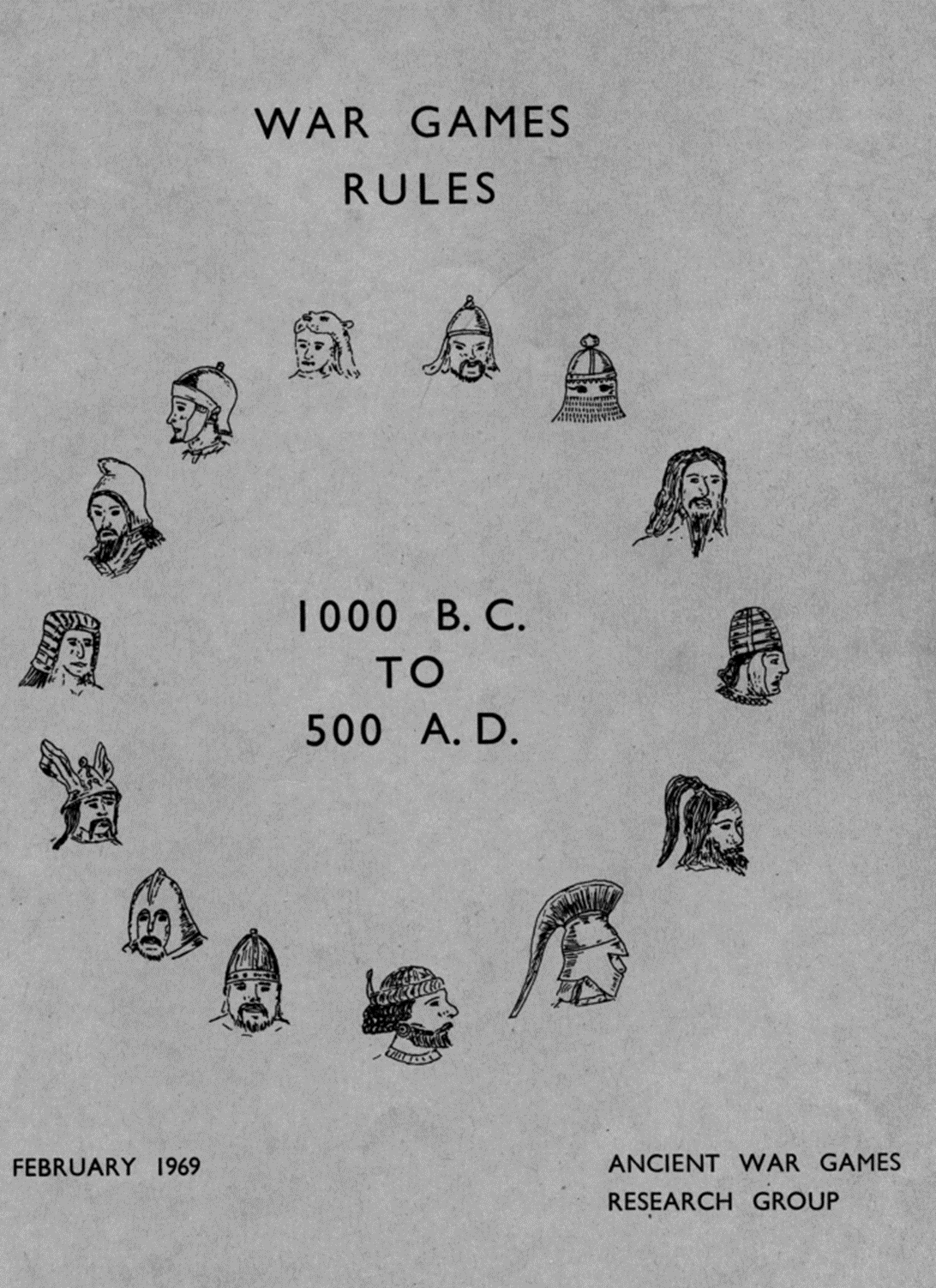

Hal, myself and a couple of friends built up forces to play games set in Middle-Earth – such as the Battle of Five Armies from The Hobbit, for which I made a tower out of a cardboard tube, and we made the battlefield by pushing books underneath an old blanket to represent the foothills of the Lonely Mountain. I believe we started off by adapting the current Wargames Research Group Ancient rules, which we were using to play Ancient wargames with mostly Airfix figures and later on Romans and Successors amongst others. That would have been the first time we’d played fantasy games in the sense folks understand the term today. The games were pretty small because we couldn’t afford many models, but they were organised into units and the games played out as little battles. I took the ‘bad guys’ whilst Hal took the human ‘good guys’ and another friend took the Elves, Dwarfs and Hobbits.

Shortly after the first ME releases Minifigs also made a range of science-fiction figures – the SF range – which we also collected. I don’t remember where the idea of SF wargaming came from, although I do recall talking to Hal about the Airfix Astronaut HO/OO plastic set and how that might be adapted to wargames. We were a bit disappointed that the figures weren’t terribly military, with only the chap pointing a hand-held camera offering any real potential! I suppose the inspiration probably came from contemporary TV series such as UFO, Dr Who and Star Trek (first broadcast in the UK in 1974). As there were no obvious rules for these new models we made up our own – including a little game that used a chess board as a grid. Once we started to make up our own games it became something of a habit, and we covered all kinds of things, historical as well as fantasy and SF, but it was fantasy and especially SF that inspired us to begin to formulate our own rules.

Minifigs Mythical Earth and Science Fiction figures from the 1975 catalogue and Airfix 01741 HO/OO Astronauts

Images from Notitia Metallicum and Plastic Soldier Review

Of course, there was a lot of time between starting out with those Minifigs ME figures and publishing Reaper, but that’s going back to the very beginning of how we started both collecting fantasy models and developing our own rules systems – as far as I remember.

How did your games and settings evolve from there?

From the mid-70s fantasy wargaming became increasingly popular and all the bigger manufacturers started to turn out ranges. Commonly, these were based on some well-known fantasy literature, such as Robert E Howard’s Conan stories or Edgar Rice-Burroughs’ John Carter books, as well as Tolkien, of course. All of these were enjoying a surge in popularity along with contemporary fantasy and science-fiction. I suppose the interest in wargaming fantasy followed the rising popularity of the genre, with contemporary writers such as Michael Moorcock, Anne McCaffrey and John Norman, as well as re-issued golden-age writers such as HP Lovecraft, Howard, Lord Dunsany, Clarke Ashton Smith and August Derleth. As a genre, ‘fantasy’ and its modern iterations in the form of speculative-fiction were very much part of the prevailing counter-culture, and you can see the influence in contemporary art and music as well, with Rodney Matthews and Roger Dean, Led Zeppelin, King Crimson and so on. So, what I’m suggesting is “there was a lot of it about” not to put too fine a point on it.

As I recall, as teenagers Hal and I did tend to undertake projects together, collecting opposing forces for historical games or collaborating to create new games for fantasy or science fiction themes. I suppose we were inspired by whatever model ranges were new and exciting at the time. The gaming circle in Lincoln met at the local wargames club, and we made friends with gamers from the surrounding area, some of whom would join in with us or lead various projects of their own. These were often historical games. I remember some of the club guys were only really interested in naval warfare and they’d set up these games with ships, which we’d all join in with. Others were more interested in World War Two or Napoleonics. I feel that I always gravitated towards fantasy subjects, whilst Hal was a bit more eclectic, but perhaps that’s just hindsight. Hal had a large micro-armour force of contemporary Russians at a time when everyone was collecting micro-tanks, for example. So, sometimes I’d be off with some of my friends who were more fantasy focussed, and Hal would be doing something else, but when it came to rules writing or ideas for games we’d often get together and bounce ideas about.

I think the first time we managed to get fairly big armies together was actually for ancients rather than fantasy, with several of us amassing good-sized armies that enabled us to play games with 2 or 3 players a side. Those games would often be played round at Hal’s parent’s house – which Hal rented off his parents when they moved out – and quite often on the floor. The current and practically universal rules used were the Wargames Research Group Ancient rules (WRG Ancients), which went through several editions over the years as well as periodic updates (for which please send stamped Self-Addressed-Envelope… those being the days!). I mention this, amongst all the very many sets of rules we bought and often played, because I think the core processes of movement, shooting, combat and morale provide the basis for wargaming any ancient/medieval/fantasy subject. When it came to writing our own rules for fantasy battles, the ‘shape’ of the game was very much influenced by those ancient wargames, even if the rules themselves owed little to the WRG mechanics.

The WRG Ancients War Games Rules (1969), The Old West Skirmish Wargames (1974) and the original Dungeons & Dragons rules (1974)

Of course, the big upsurge in fantasy came about with Dungeons & Dragons, which led to much more interest generally and new figure manufacturers including Asgard Miniatures based in Arnold, Nottingham. I played a bit of D&D with a couple of my wargaming buddies, but I don’t recall that Hal was ever part of that, he moved out of Lincoln to Nottingham when he went to university where he would mix with a different crowd, including some of the Asgard team and hangers-on. When I say I played a bit of D&D, you have to remember this was the very loose format 2nd edition, which had a huge element of “make it up as you go”. I remember drawing up plans for medieval monasteries to play games with a more historically credible kind of fantasy – as opposed to the original American-flavoured version – sort of The Name of The Rose with daemons!

By the time D&D hit the UK we’d already been playing fantasy skirmish wargames with proto-role-playing elements inspired by The Old West Skirmish rules published in the early 70’s by Mike Blake, Ian Colwill and Steve Curtis. This was a highly detailed set of rules in which players assumed the identity of a particular character in games created and run by a games master, with incidental characters acting either as followers of the main players or games master controlled individuals. Characters could suffer wounds that would have to be taken into account during future games, but could also gain abilities by experience, albeit in a fairly free-form fashion largely dictated by the games master. In other words – although not quite role-playing – many of the ideas that made role-playing distinctive were already there in The Old West Skirmish game. Indeed, it’s not unlikely that the originators of D&D had at least some passing familiarity with the game, as both sets of authors contributed to Donald Featherstone’s Wargamer’s Newsletter magazine and were certainly aware of each other. Be that as it may, inspired by the rules ideas in that game together with background ideas at least partially inspired by Michael Moorcock’s Runestaff books, Hal ran a fantasy/SF crossover wargames campaign set upon a future post-apocalyptic Earth which (via means of teleportation) took us to a semi-terraformed Mars. The rules Hal and I developed for that campaign would become Reaper.

Reaper, first edition (1978), Combat 3000 (1979) and Laserburn (1980)

How did Reaper, your first fantasy rules, and Combat 3000, your first science-fiction rules, come to be published?

Hal and I were really keen to see our game published and, because Asgard Miniatures had just started up and we rather liked the Asgard models, we got in touch and asked if they’d be at all interested in publishing our game. It was of course Bryan Ansell we spoke to, and who invited us over to see the Asgard operation and who would go on to help us publish Reaper. Both Hal and I got to know Bryan, me painting and sculpting a little, while Hal contributed articles to Bryan’s role-playing fanzine Trollcrusher. By then Hal had moved over to Nottingham, where he started a politics course at the university, whilst I was still in Lincoln having left school but still a year out from going to university in Lancaster. So, Hal was a year ahead of me, having left school a year before me, which meant that our wargaming worlds were somewhat divided, but Hal would often drop in on me on his way to see his parents, when much tea was drunk and wargames news and plans exchanged. We must have put the rules for Combat 3000 together over that period, the supplement certainly belongs to the days when Hal was in Nottingham as you can tell from the marvellous Nick Bibby illustration of the various play-testers and miscreants who helped playtest the game – Nottingham gamers all.

Combat 3000 was really our second project aimed at publication. I seem to remember it was much more focussed exercise than Reaper and must have been a must faster turn-around. Looking back on it is feels a little underplayed – the rules element is well enough worked out but as a concept it lacks something of the charm and whimsy that is evident in Reaper. I think whereas Reaper was put together by me from Hal’s core rules and my additional material – notably the magic system – Combat 3000 was more Hal’s project with me helping with development and playtesting. The only thing I can think that I contributed directly are the rules for some of the alien types – particularly the Quofan – because I remember building up the Quofan models from Asgard Owlbears and adding helmets, weapons and futuristic gear from milliput. Looking back, it’s a shame that we didn’t include more background material, as we certainly had an idea of a universe when playing games, because I think that would have helped give the game an identity. If you compare Combat 3000 with the much more well known Laserburn from Bryan Ansell, which came out some years later, the main difference is that Laserburn feels like it belongs in a definite place, whilst Combat 3000 has a sense of being a set of rules you can adapt to suit your own backstory.

What was your Combat 3000 setting like? Was it a proto-40K? Bryan Ansell has said your and Hal’s “Imperium” setting was the origin of WH40K‘s Space Marines.

As I recall our setting was much more along the lines of Blake’s Seven, in which our protagonists were rebels and piratical types, ne’er-do-wells on the make and such like. There were various industrial manufacturing cartels, which gave us the names for some weapons. It wasn’t really a game aimed at fighting big battles with armed militaries. It was more ‘the wild west’ in space, although we may have expanded it simply to facilitate the various Asgard models for which we provided stats. It certainly wasn’t proto-40K. The idea of armoured warriors in space – well that comes from classic SF like Starship Troopers, I suppose, but Bryan did design similar armoured warriors for Tabletop Games, and Asgard made similar things too, so it wasn’t exactly an original concept. The idea of making them a medieval military order… in space… with that direct relationship to their ‘god’… was something I came up with as I wrote 40K. I don’t think that has any precedent in any previous game setting as far as I know. The closest things I can think of are the 2000AD comic strips Nemesis and Rogue Trooper.

Combat 3000 mentions another set of science-fiction rules that you and Hal were commissioned to write, but which was not published. Reaper’s first edition also mentions a future science-fiction version, which might be the same game. What happened?

I don’t remember any set that was commissioned but not published – perhaps something Hal was discussing with Bryan and Asgard at the time. As for the Reaper throw-away comment, well, we did use Reaper for cross-over games – the system was built for that and there were even SF elements like ‘flame lances’ in the rulebook. Sounds like something we would have liked to have done, but as far as I know it wasn’t taken any further.

Can I briefly pick up on your comment on the Reaper magic system? It was quite an unusual system, providing the building blocks for creating custom spells, instead of pregenerated spell lists. I think the only similar ideas at the time were Isaac Bonewitz’s Authentic Thaumaturgy (1978) and Chivalry & Sorcery (1977), which was based on Bonewitz’s earlier book Real Magic (1972). Was your system influenced by any of these, or did it come from somewhere else?

I just made it up! I’m not familiar with Bonewitz – so it definitely wasn’t inspired by that – and although we had a copy of Chivalry and Sorcery about the time we were developing Warhammer role-play, Reaper was years before that so I can’t imagine there’s any inspiration drawn there either. I developed an interest in such things reading Dennis Wheatley and I had read a little about the Order of the Golden Dawn – mostly because we studied WB Yeats for A level – but that’s about it. When Hal and I produced Reaper, we had this idea that it was a set of very adaptable rules that players could use within their own fantasy universe – I think that at the time we would have considered it ‘pretentious’ to present players with a world background – the emphasis was on building a tool that allowed players to build their own imaginative constructs. I know that sounds weird – given that these days ‘fantasy’ is often all about back story – but that wasn’t how we saw it. We wanted the freedom to do our own thing, and we assumed everyone else did too. I think this was especially the case with Hal – who was more interested in creating playable mechanics with a clear route to success or failure – whereas I think I was always more interested in games with a strong narrative. If you look at Combat 3000 you’ll see it’s the same thing – there’s the structure for a game but no explicit back story to the setting. The magic system follows that idea – it allows you to create your own spells to suit whatever back story you care to invent – the limited background I added is by way of example. I think that’s what lies behind the methodology of the magic rules, rather than an attempt to model ‘real’ magic as such.

To turn to Warhammer’s first edition, there were snippets of a setting at that stage: places like Aran-sul, Borunna, Caraz-Adul and Caraz-a-Carak, and a Tolkienesque Necromancer of the North with a magic sword Nec-Tomun. Can you tell me more about these and where they came from?

That’s so long ago! They were just invented on the fly to give context to the magic items. Interesting that I came up with Caraz-a-Carak (with C rather than K) so early and it obviously stuck. There’s an evident Tolkien-like quality to much of the background pieces as you say. That’s the case even with the humorous descriptions in the Book of Battalions enclosure, where the relationship between the Dwarfs and Elves is antagonistic to the point where one of the Dwarf characters is suspected of having ‘Elf’ sympathies and leads a lonely life writing elven poetry, shunned by his kinsfolk and not trusted by the soldiers sent to ‘serve’ him – in truth to keep an eye on him!

The piece about the Dwarf realm of Caraz-Adul and Caraz-a-Carak reminds me that I had a potential supplement for Dwarfs on the go about this time – because I had worked out a lot of material about the Dwarf language to go with it. Caraz-a-Carak means ‘stoney stone place’, or ‘eternal stone place’, where a Dwarf proper noun also stands for an abstract noun (stone and eternity) and where the suffixes give you the context – which is – of course – the origin of Karaz-a-Karak, or Everpeak, in the Warhammer World. I never did finish that supplement, but I must have retained a lot of it in mind because I used that system of language to work out all the subsequent Dwarf place names. When we published the army book for Dwarfs for the 4th edition, I went back and re-worked the Dwarf language description, and Nigel Stillman and I added more. So, it did get used in the end! As for the rest of those names from the first edition magic section, well they came and went along with so many other pieces of short entertaining descriptive text that just encapsulated an idea or gave something a bit of character or context. Just shows you how an idea can take root and grow into something worthwhile.

Was there a particular reason you chose to produce a supplement on dwarfs? Were you planning to do supplements for multiple Warhammer races over time?

I think it was just something I fancied doing – I was always intrigued by Tolkien’s treatment of Dwarfs and I think that inspired me to explore the idea for Warhammer. Thinking back, I’m not sure whether that would have been WH1 or 2 to be honest – pre-3 for sure – probably around the transition. Also, I seem to remember I was thinking in terms of a dungeon environment along the lines of Moria. I think you can see that influence in the World Edge Mountains and the various Dwarf strongholds. I’ve a vague inkling I was working towards a dungeon-style group adventure setting with a specific, but small, Dwarf stronghold set deep at the head of a valley. I must have given up on that fairly quickly. The only legacy is the rudiments of the Dwarf language, which I used to name the various Dwarf strongholds in the World’s Edge Mountains.

The Book of Battalions (1983) and Warhammer Armies: Dwarfs (1993)

Various other bits and pieces were added to the nascent Warhammer setting in early Citadel flyers, for example, Chrystol, Horvenghaast and the Empire of the Four Nations. Can you shine any more light on them?

The names and places from the flyers I don’t recognise at all. I suspect they may have been pieces from Bryan because he would have worked up the flyers before I took over, and – although I don’t remember to be honest – there must have been a short period when Tony Ackland was putting the flyers together and Bryan was working out the deals and text rather than me. I might have been typing up Bryan’s text or possibly that would have been done by Tony Ackland or Diane Lane (Bryan’s partner and later wife – who ran the office side of things in Newark). Bryan did continue to come up with ideas and short pieces during the evolution of Warhammer – ‘The Duelling Circles of Khorne’ is something I remember – which I think evolved into Bryan’s first draft of Realm of Chaos. That draft outlined the four chaos gods, demons, warriors, beasts, hounds, and beastmen, and provided charts for random generation of chaos attributes, rewards, chaos gifts – basically all the material that would form the core of the published Realm of Chaos books years later. Tony and I had gotten a long way towards finishing the paste-up for the Realm of Chaos supplement before it was put aside and we produced the second edition of Warhammer instead. Unlike Hal and myself, Bryan didn’t type, so he’d write everything in longhand on individual sheets of paper. But he contributed pieces – or ideas for pieces – to the Journal and Compendium and would often attach names to models he’d incepted. I’m guessing that at least some of those names you list came from Bryan – but it’s only a guess!

The flyers also mention Bryan’s “gigantic Chaos Saga” and gods like Heinous Suth and Wenwoch the Waylayer.

I think Bryan’s “gigantic Chaos Saga” is a reference to that Realm of Chaos project – which, as I say, was a good way along before it was put aside. We had a cover piece from John Blanche, which I believe hung in Bryan’s house at East Stoke, portraying a warband in all its mutated glory. It certainly was gigantic. Bryan loved random generation tables – he was ultimately more interested in the narrative and character of a game than its purely competitive quality – he liked mechanics and ideas that were engaging in themselves – hence all the random generation tables. The Realm of Chaos was a showcase for all of those things. The trouble was, Bryan kept adding more to it, and I struggled to keep updating all the tables and charts. This was especially difficult because the word-processor technology wasn’t all that sophisticated and every time something was added to a table, I had to re-calculate and re-type the entire thing. We very quickly ended up with a D1000 table for chaos mutations.

John Blanche’s original cover for Realm of Chaos

Wenwoch the Waylayer and Heinous Suth – those are from the Knights of Chaos boxed set -which was the third Chaos boxed set after Warriors and Champions. If you look at the names for the first two boxed sets, they are rather standard fantasy stuff – Bloodaxe Gut-ripper, Arkon Stormrider – I imagine those would all have been named by Bryan or – at least – not by me. By the time the third box came out I’d taken over providing the box text and I came up with the names. I just did what I did for the game writing – I added some entertaining epithets to try and evoke a context – so those names were just invented for that purpose. I remember I did have to run the names past Bryan, who made me change a couple of them because he thought they were rather too silly! I think this was done before we started on the Realm of Chaos project proper – so before Bryan came up with the definitive four gods, when the idea of ‘chaos’ was a little more chaotic.

Part two of the interview follows here.

For my other interviews, see this link.

Title art by John Blanche. Internal art by John Blanche, Tony Ackland et al. Used without permission. No challenge intended to the rights holders.

Aces!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Fascinating stuff! This is all delving into history that is before anything I’m familiar with. It’s really interesting reading about the context that Warhammer grew out of.

Really looking forward to the next part!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Can someone explain to me the pun or reference for the Nec-Tomun sword?

LikeLike

Not me. I am not entirely certain there is one.

LikeLike